A collaborative research effort between the laboratories of Qingyun Li, PhD, assistant professor in the Departments of Genetics and Neuroscience, and Harrison Gabel, PhD, associate professor in the Department of Neuroscience at Washington University School of Medicine has uncovered fundamental mechanisms that govern how microglia—the brain’s resident immune cells—adapt their functional states across development, aging, and disease. The study, “State-specific enhancer landscapes govern microglial plasticity,” was recently published in Immunity. Microglia are increasingly recognized as key players in neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative processes, yet how they transition between functional states over the lifespan has remained unclear. In this study, the research team demonstrates that these transitions are not fixed lineage decisions, but rather reversible and highly plastic state changes governed by epigenomic remodeling—specifically, dynamic histone modifications at state-specific enhancers.

The work was led by co–first authors Dvita Kapadia, who conducted the research as a research technician in the Li lab and is now a PhD student at Washington University, and Nicole Hamagami, who was an MD, PhD student in the Gabel lab at the time of the study. Their combined efforts were central to integrating genetic fate mapping, transcriptomic analyses, and epigenomic profiling across developmental and disease contexts.

Using genetic fate mapping, single-cell transcriptomics, and advanced epigenomic profiling approaches, the team tracked microglial populations from early postnatal development through adulthood, injury, aging, and Alzheimer disease models. Researchers used a novel genetic mouse model developed by the Li lab, which enabled precise labeling and long-term tracking of specific microglial populations as they transitioned between developmental, homeostatic, and disease-associated states.

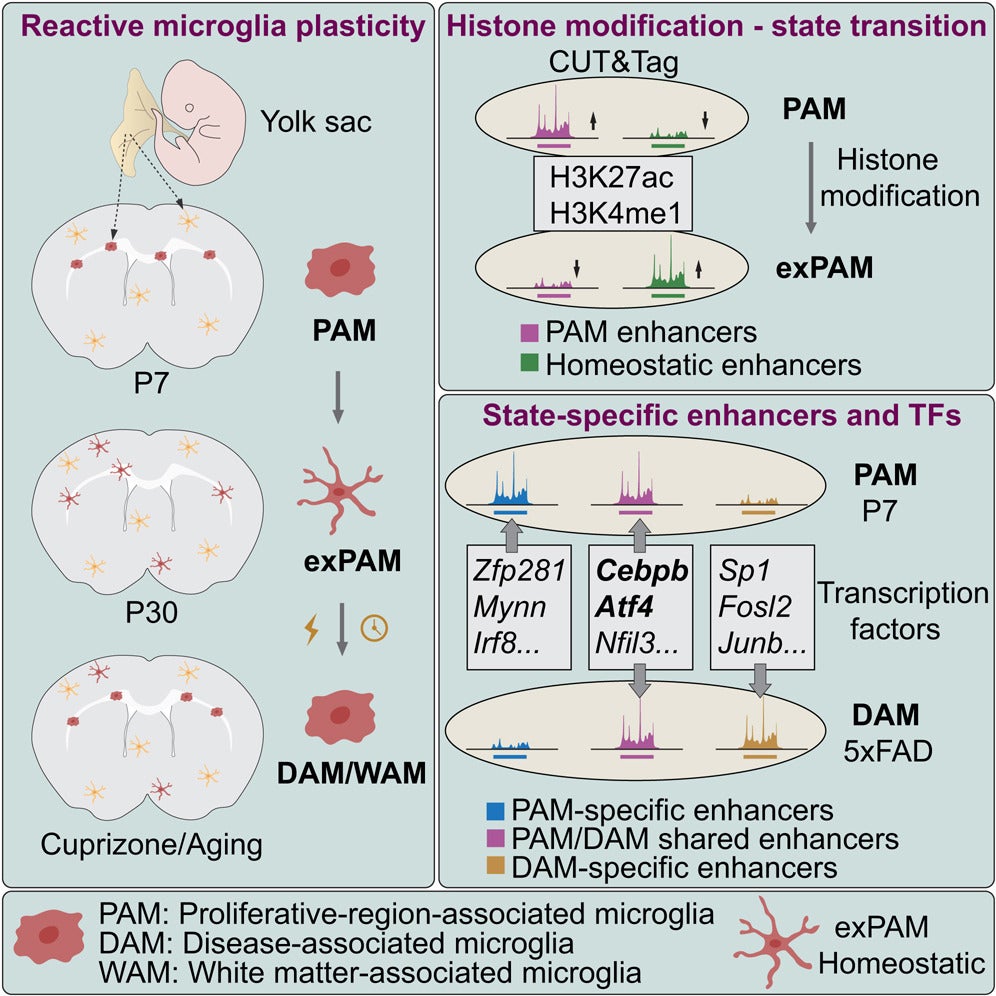

The findings reveal that proliferative-region-associated microglia (PAMs), which emerge during early brain development, can later convert to homeostatic microglia and subsequently re-enter reactive states, including disease-associated microglia (DAMs) observed in neurodegenerative disease, as well as white matter–associated microglia (WAMs) that emerge during aging.

A key discovery of the study is that histone modifications—rather than DNA methylation—drive microglial state transitions, with distinct enhancer landscapes and transcription factors controlling these changes. By integrating epigenomic and transcriptomic data, the researchers identified regulatory elements shared across developmental and Alzheimer disease–associated microglial states, providing a unified framework linking microglial function in health and neurodegenerative disease. These findings also suggest that epigenomic signatures established during early development may influence microglial responses later in life.

“By defining the enhancer programs that control microglial state transitions, this work provides a foundation for designing future therapies that more precisely target disease-associated microglial states,” said Li. “Understanding these epigenomic mechanisms opens new possibilities for modulating microglial function in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders.”