Early Years

The Department of Genetics at Washington University in St. Louis formed in 1975, but its roots date back a few years earlier. In 1967, a review by the School of Medicine called for financing a major department of genetics. Later that year, William H. Danforth, MD, vice chancellor for medical affairs at the medical school, announced that the James S. McDonnell family had made a pledge of $1.4 million to establish a Department of Genetics. The McDonnell family had already funded a medical science building, so their support for a new genetics program was “particularly appreciated,” Dr. Danforth noted in his remarks.

Genetics Department Formation

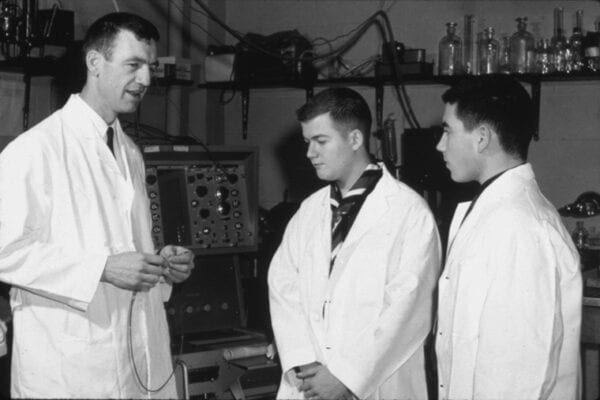

In 1975, Washington University appointed Donald C. Shreffler, PhD, as the acting head of the new Department of Genetics. Dr. Shreffler was recruited from the University of Michigan and brought his colleague Chella David, PhD, along with him to the new department. Later they recruited Ted Hanson, PhD, and together their studies on the mouse H2 system ended up playing major roles in immunologic research and establishing the mouse as a model for understanding the genetics of organ transplantation.

Donald C. Shreffler Lecture

The Donald C. Shreffler lecture was established in 1995 through a generous gift from Mrs. Dorothy Shreffler and sons, Dave and Doug, to honor the contributions of Donald C. Shreffler, PhD, to Washington University in St. Louis and the scientific community. This lecture historically has featured scientists whose work utilizes the mouse as its model for genetic analysis and each year brings an eminent mouse geneticist to Washington University to speak in this lectureship.

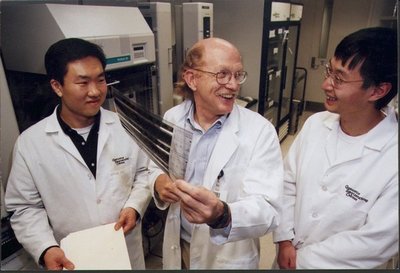

Dr. Shreffler soon recruited Maynard Olson, PhD, to join the new department. Dr. Olson’s goal was to produce a map of the entire yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. In creating this physical map, his laboratory developed mapping techniques that were instrumental in propelling the Human Genome Project.

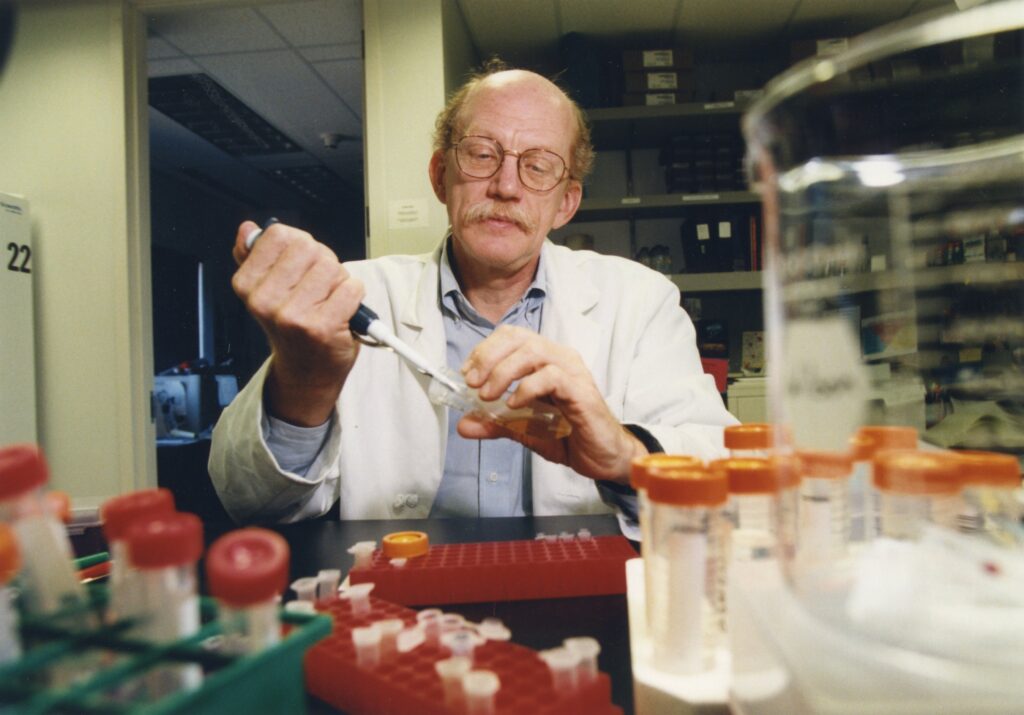

In 1976, Robert H. “Bob” Waterston, M.D., PhD, joined Drs. Shreffler and Olson. Dr. Waterston came to Washington University from Cambridge, England, where he was a postdoctoral fellow at the Medical Research Council (MRC) Laboratory of Molecular Biology. He initially joined Washington University’s Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology before moving to the Department of Genetics.

Bob Waterston,

MD, PhD

joined the Washington University School of Medicine in 1976 and served as the Genetics Department Chair from 1991 to 2003.

The next year, Dr. Shreffler was named James S. McDonnell Professor and Head of the McDonnell Department of Genetics at Washington University School of Medicine. He recruited additional faculty, including Robert Paul Levine, PhD, who was appointed Professor of Genetics, and Robert G. Roeder, PhD, who was appointed Professor of Biological Chemistry and Genetics, funded by an endowment gift from James S. McDonnell.

Department Expansion in the 1980s

The 1980s was a time of international and scientific expansion for the Department of Genetics. This extraordinary time laid the groundwork for many of the technologies that launched the human genome project.

As just one example, in 1986, David Burke, a graduate student in Maynard Olson’s lab, developed a system of cloning large fragments of human DNA in yeast artificial chromosomes. This work became the backbone for much of the department’s human genome sequencing efforts throughout the next decade.

In 1987, Dr. Olson and David Schlessinger, PhD, a professor of microbiology at Washington University, formed the Center for Genetics and Medicine with a grant from the James S. McDonnell Corporation. The center set up a core facility that focused on four areas of research and technological development, including building an information handling system that would become central to the informatics analysis of the sequencing project. The facility also developed the first human libraries in yeast artificial chromosomes for use in mapping and sequencing projects.

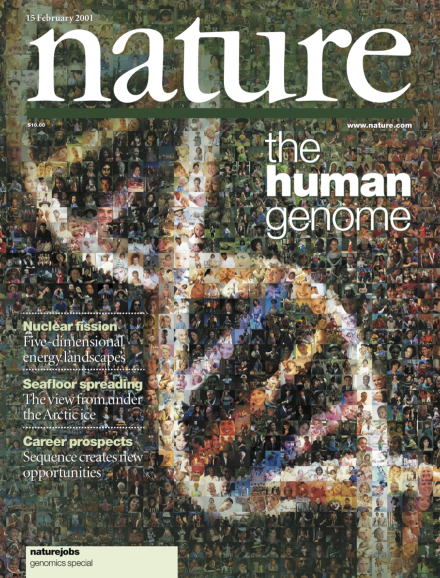

The Department of Genetics and the Human Genome Project

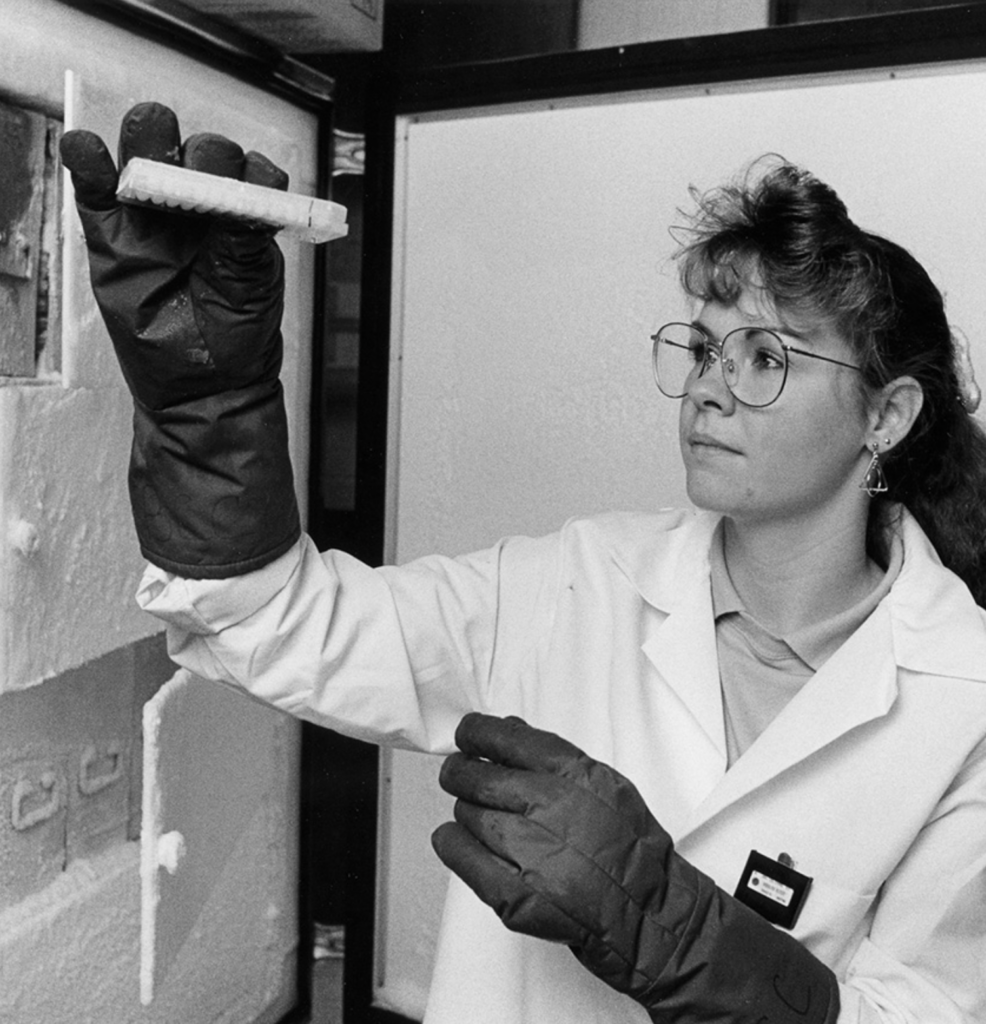

Meanwhile, Dr. Waterston focused on large-scale sequencing. In the late 1980s, he took a sabbatical in Cambridge to work more closely with John Sulston and Alan Coulson at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology. Waterston and his colleagues concentrated on developing plans and reagents to sequence the genome of the nematode C. elegans.

In 1990, Dr. Waterston started the worm genome sequencing project. He received a three-year grant to support the collaborative efforts between his lab and the Sulston and Coulson groups. This partnership led to the sequencing of the entire worm genome, a major milestone in genomics. It was the largest genome sequenced at the time and laid the foundation for the major role played by the Department of Genetics in the Human Genome Project.

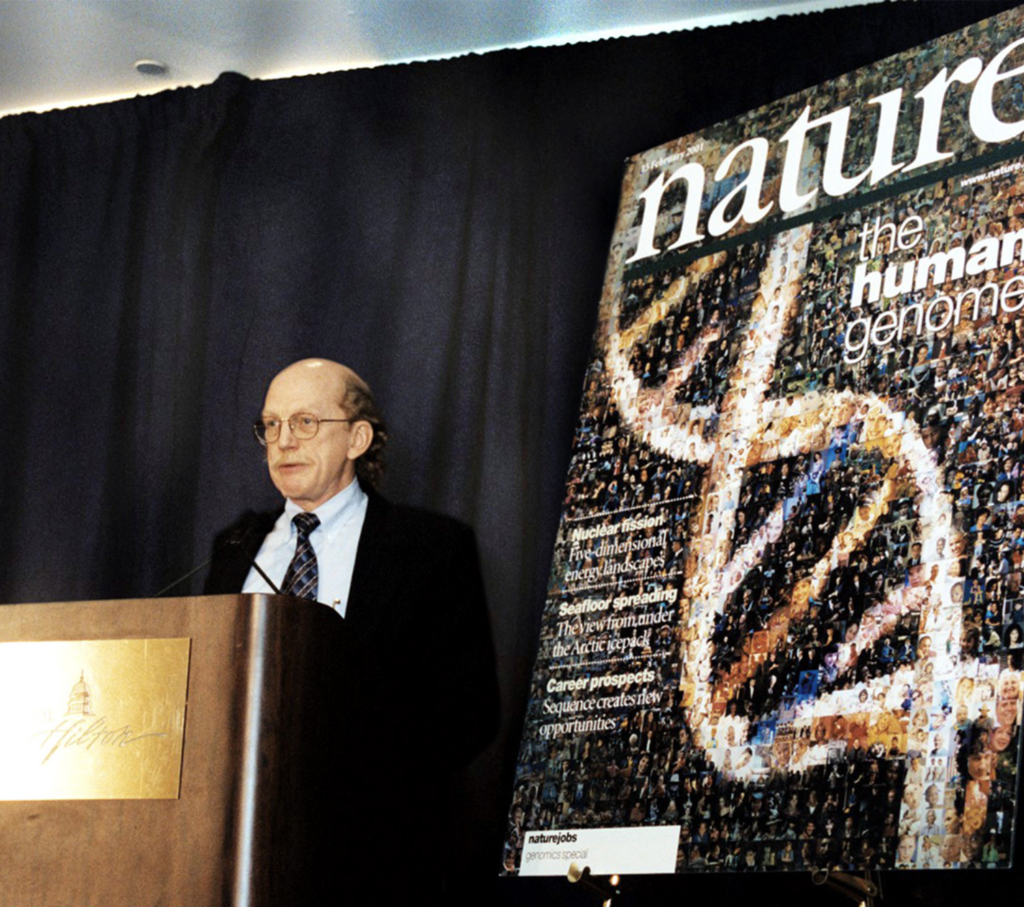

The same year, Washington University School of Medicine was designated one of the Public Health Service’s first four centers of investigation for the federally funded Human Genome Project—the genesis of the Genome Sequencing Center. The Genetics Department received $2.3 million for the first year of a 5-year grant to support the sequencing efforts of this nascent Center. Dr. Schlessinger was named director of the new Genome Sequencing Center (GSC), a position that was later assumed by Dr. Waterston.

In 1991, scientists in the department, including Drs. Hartl, Olson, Waterston, Schlessinger, Johnston, as well as Helen Donis-Keller, PhD, and Philip P. Green, PhD, teamed up to begin deciphering the human genome. They developed and applied methods such as using PCR to identify sequence tagged sites and yeast artificial chromosomes to enable the rapid ordering of DNA fragments. These ordered, overlapping fragments provided the necessary structure to begin piecing together the sequences of these human DNA clones, a strategy that was used for much of the sequencing of the human genome.

Around this same time, Dr. Eric Green, M.D., PhD., a Washington University School of Medicine alumnus and resident working in Dr. Olson’s lab, was appointed as Assistant Professor of Pathology and Genetics and named co-investigator of the Human Genome Center. By 1994, Dr. Green would join the freshly established Intramural Research Program of the National Center for Human Genome Research, or what is known today as the National Human Genome Research Institute, where Dr. Green still serves as Director.

A major milestone in the Department’s human genome research occurred in 1993 when Dr. Waterston received a $29.7 million grant to continue his work on the Human Genome Project. The 5-year award was aimed at completing the entire C. elegans genome and begin the work of sequencing several human chromosomes.

Building on Past Foundations, Breaking New Ground

In 2009, Jeffrey Milbrandt, MD, PhD, was named the James S. McDonnell Professor and Head of the Department of Genetics. Dr. Milbrandt joined Washington University in 1983 as Assistant Professor of Pathology and Medicine. His laboratory focuses on axon degeneration, a primary cause of neuropathy and many other neurodegenerative conditions. He brought a new vision to the Genetics Department that focused on using genetics and genomics to improve human health through better understanding of the molecular underpinnings of disease.

The Genetics Department strives to foster an environment that brings everyone together so that the School of Medicine can be a leader in personalized medicine. The Department has built world-class centers to expedite the application of novel genetic technologies to medical research and have developed deep collaborative relationships with our clinical and basic science colleagues.

McDonnell Genome Institute (MGI)

The McDonnell Genome Institute originated from the work of Dr. Waterston’s Genome Sequencing Center and continues to break ground in omics technology access today under the direction of Dr. Jeffrey Milbrandt. From contributing 25% of the finished sequence to the Human Genome Project to sequencing the first cancer genome, up to today’s innovative COVID-19 testing, MGI’s research continues to advance the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease.

Over the past decade, we have strengthened our presence in model organism genetics, gene regulation, computational biology and human statistical genetics, and pursued new areas of interest in genome technologies, neurological disorders, cellular bioenergetics, and personalized medicine.

These new frontiers of research represent the work of Joe Dougherty, PhD; Tychele Turner, PhD; Peter Jin, PhD; Ting Wang, PhD; Samantha Morris, PhD; Michael Meers, PhD; and Gabor Egervari, MD, PhD, among others. The Department’s early and mid-career cohorts have brought new expertise and renewed energy to the Department, with a focus on mechanistic disease-based work along with computational and advanced genomic analyses.

Looking to the Future

The Department of Genetics is well-positioned take advantage of new opportunities afforded by the new era of genomics in our own laboratories and in collaboration with colleagues performing more translational research. Coming out of a sustained period of significant financial success, the department is ready to pursue aggressive growth plans over the next several years.

Ting Wang, PhD, a nationally recognized leader in genetics-based collaborations, eagerly accepted the chairmanship of the Department of Genetics in August 2023 and immediately put plans into motion to expand the faculty. Investigators in all areas of genetics and genomics have been encouraged to apply, with plans to solidify those fields where the Department is already a leader and break ground in new and exciting areas.

Through these efforts, the goal for the Department and everyone involved in its work remains the same: achieve fundamental discoveries contributing to the world of genetics and genomics, and rapidly translate these into applications that benefit humankind.