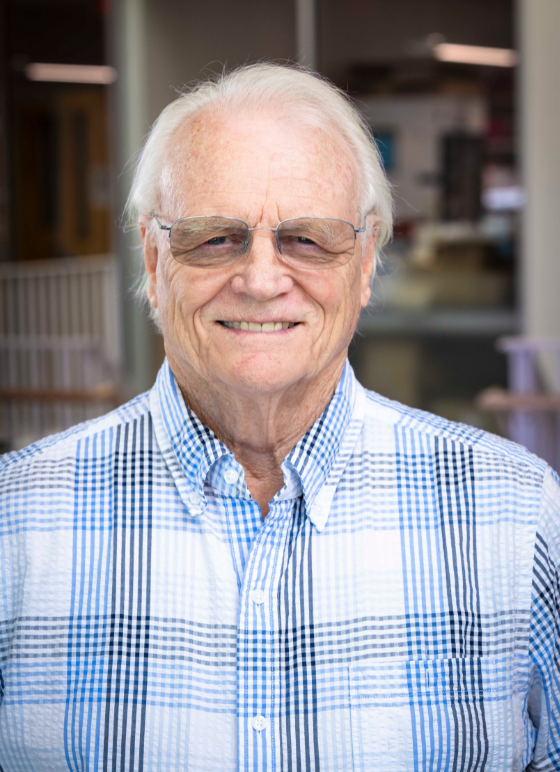

After 24 years of professorship at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Dr. Gary Stormo, the Joseph Erlanger Professor of Genetics, retires at the age of 73.

A pioneer in the field of bioinformatics and genomics, Dr. Stormo was the mentor of many students and scientists. One of his biggest contributions at the Department of Genetics at WashU is establishing the Computational Biology Program (now called the Computational and Systems Biology Program) in the year of 2001 which was one of the first computational biology PhD programs in the world at that time.

On December 15th, 2023, around 150 faculty, students and staff joined the holiday party at the Department of Genetics and made a toast to Dr. Stormo for his retirement. “Gary is a real giant in the field of computational biology!” said Dr. Ting Wang, the Chair of the Department of Genetics. Wang is an internationally recognized geneticist who was the first student in the Computational Biology Program established by Dr. Stormo. The program recruited 2 students for its first year in 2001 and has grown steadily for two decades, with 10 new students joining in 2023.

Computational Biology Program at WashU

In 1999, Dr. Gary Stormo moved from University of Colorado to Washington University in St. Louis to start the Computational Biology Program. The program started recruiting students in the year 2000 and had its first starting class in 2001. In addition to Dr. Gary Stormo, the program was run by well-known bioinformaticians and computational biologists such as Drs. Sean Eddy, David States, Michael Zuker, Warren Gish and several people with expertise in computational biophysics of protein structure.

Initially motivated by deciphering the large sequencing data generated by the Human Genome Project (1990-2003), the program focused on sequencing analysis. However, the focus of the program has evolved over time. Nowadays, the ability to handle data is almost required for any biological research. Thus, the program has evolved to train students to think quantitatively and be able to handle large sets of data. Students with these skills can apply them to a wide range of topics within the field of biology and biomedical research. As a result, Computational Biology plays a key role in promoting interdisciplinary research. “Our students are probably in more diverse departments’ labs than students from any other programs.” said Dr. Ting Wang, “Because they bring quantitative skills into all the different disciplines in life sciences, whether it’s neuroscience or microbiology for instance.”

Below is our interview with Dr. Gary Stormo

How did you become a scientist?

My parents moved to California when I was in 2nd grade, so I grew up mostly in southern California. I went to Caltech as an undergraduate. I’ve always been interested in science, so when I had the opportunity to go to Caltech, it was an easy decision. I was going to be a physics major, but I switched into biology because there were a lot of exciting things happening in biology at that time. Then I went to graduate school in Colorado and got interested in studying gene regulation (how genes are turned on and off). Initially, my project was to use this very laborious way to sequence a little piece of DNA that we knew had a little regulatory signal in it and we were trying to figure out what’s going on.

What led you to study computational biology?

Fortunately, at the beginning of my career, two different revolutions were happening. The first one was the ability to sequence DNA which happened when I was a graduate student. The second one was the computer revolution. In the middle of my graduate career, suddenly people can sequence lots of DNA as previously I thought it would take me 3 to 4 years to sequence a little piece of DNA. So not only did we generate sequence ourselves, but everybody else was generating sequence and publishing it. And it quickly became a case where there weren’t any tools to analyze the sequences. Another student who joined the lab I was in had a fair amount of computer science background, so we just decided that there was an opportunity to start writing programs to analyze DNA sequences.

One of the first things I did, and it was part of my PhD, was to use an early form of AI which was a very simple pattern recognition method. It turned out to work better than most things people had tried before. So suddenly we had ways to represent and search for signals in DNA that were important for controlling gene expression.

Then over the next 10 years, this field exploded. We developed algorithms to do motif discovery. The other revolution that people don’t really think too much about is the ability to synthesize DNA was also invented right around that time. So that meant that you could make your own DNA sequence to test various hypotheses.

One of the first things we started doing was to make random DNA and then have some biological assay for its function that will also allow us to figure out what’s important in the DNA, what the signals are that control gene expression. It was a conjunction of new technology in terms of the biology, the sequence and synthesize DNA and the combination of that with computers rapidly coming on. We started collaborating with people in computer science, they helped us get started and gave us good ideas. We also collaborated with people from statistics and physics. It was a really exciting time with new kinds of data that helped us understand biology.

Can you go over the timeline of all the technological developments in your field?

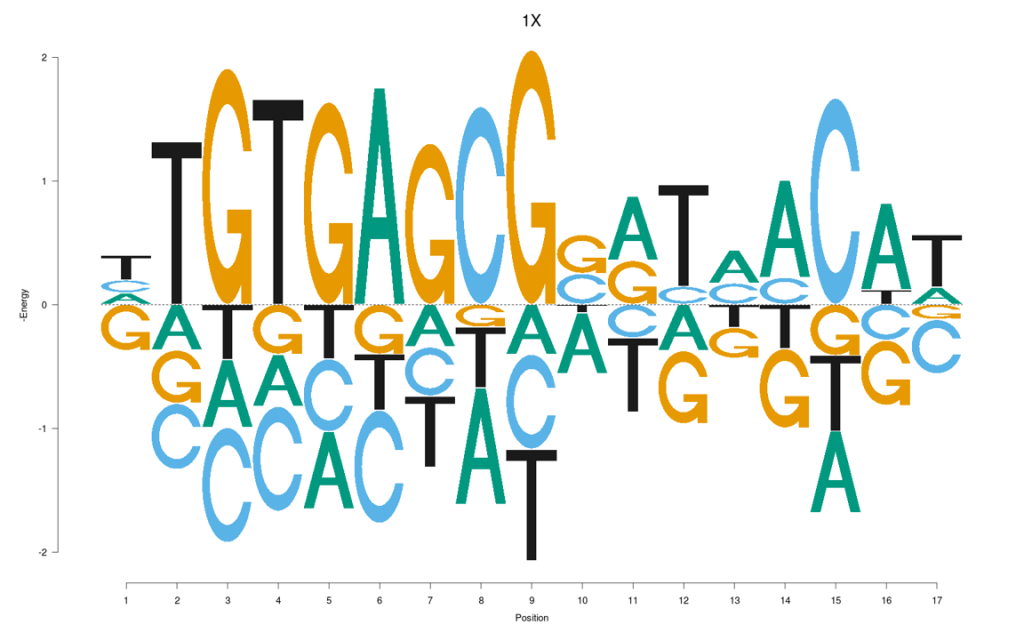

DNA sequencing was invented in 1977 when I was a graduate student. I got my PhD in 1981, and for the next 10 years, all those things I was talking about were happening. We invented the Position Weight Matrix model to represent DNA which came out of my thesis. The other student I was working with brought information theory into the whole thing, so we were looking at probabilistic models, and we were using synthetic DNAs to test and understand how things worked even more. That was all in the decade from 1981 to 1990.

There were a few other problems we worked on. We started studying RNA structure which was also interesting at that time. One of the problems we worked on early on was gene prediction. When people were generating DNA sequences, you didn’t know where the genes were, so you had to predict it. In bacteria it was easy because there aren’t any introns. But in eukaryotic cells there are a lot of introns. Predicting the genes was hard. There were lots of people working on that problem including us. But then, people started sequencing RNA and it didn’t matter anymore. Because you can just sequence the product and then you’ll know where the genes are. So that was an interesting problem for a while but then it was sort of a solved problem, and nobody thinks about it much anymore.

What brought you to WashU?

In the 90s, there was an explosion of people starting to work on computer algorithms. People need to predict where the genes were from the DNA, so there was all this gene prediction stuff going on before people started sequencing RNA. So that whole decade from the 90s was really intensified by the Human Genome Project which got me really interested in education programs.

There weren’t many graduate programs in bioinformatics back then. I knew it was the right time to happen because the Human Genome Project required people to be trained. There were a lot of people coming into the field from computer science, and people from biology and they were doing cross fertilization and working with each other. I had a lot of collaborators in other fields, but there weren’t any training programs to teach students that, so I really wanted to get one started.

I was still in Colorado and couldn’t get the resources to do it there. But in WashU there were people already doing that here. There was a big Genome Center here and it was a big player in the Human Genome Project. I came to visit and told them about my goals of starting a graduate program in computational biology and there was a lot of excitement about it. That attracted me here in 1999 and it got off the ground quickly. Ting was the first student in the Computational Biology Program, and he is now world-famous and an incredibly important person in the field. It was a good coming together of things: I wanted to start a program, this is the place that had a good critical mass, people doing things already. The program was up and running in 2001. I think it’s been successful. I can look back at that as one of the accomplishments I am most proud of and all the students I’ve had.

How many students have you mentored?

I have now 25 students altogether. I had a total of 6 in the years I was in Colorado, and I had 19 in WashU. I had around 20 postdocs and I am also on the thesis committee of other students. Most of my students have gone on to the Biotech industry which has been and still is a great place where you can get good jobs. Some are in the academics, such as Takis Benos at University of Florida who is setting up a program there in computational biology and Kai Tan, at University of Pennsylvania.

About 40 years ago, the Position Weight Matrix was introduced, where do you think the future is?

It’s a tool that gives you a model for predicting where transcription factors were binding the DNA and now we know it’s an approximation. It’s not perfect by any means. But it does help people when you see variants that you think might cause a disease. If that variant falls right on top of the Position Weight Matrix predicted binding site, then that gives you a hint that maybe you found a variant that alters gene expression. That’s been reasonably successful. It’s just a tool that people use to understand what a sequence means and especially where the signals are for gene regulation. Weight matrix is sort of a general term, and it has different uses in different specific ways that people build them. That general idea is still used all the time.

If you’d start over again would there be another field that is exciting to you that you were not able to get into?

I was there at a very lucky time, the conjunction between revolutions of DNA sequencing and synthesis and computers, so at that time I picked the right thing. Looking back, are there any opportunities I missed, I probably would spend more time learning about AI. I used a very simple early form of AI then I sort of stopped doing that. So I might spend more time doing AI. I would have taken better advantage of synthetic DNAs. We were the first groups to start using random DNA, but now people like Barak Cohen use synthetic DNAs in really powerful ways that I really never got into. So I might do that. But really, when I look back, I can find little things that I wish I had learned more about. Overall, I’m pretty happy with the way things turned out and I wouldn’t change a lot.

Did you always know you were going to be a scientist when you were a child?

I think if you ask me when I was in elementary school, I would say I was going to be an inventor. I always did well in math and science, and I knew pretty early that’s what I wanted to do, once I gave up hope of being a baseball player.

Was it hard to get into Caltech back then?

I only applied to three places, and I got into all of them. The two I really wanted to get in were either Stanford or Caltech and I got into both. I think if you know you are going to be a scientist, you can’t really beat Caltech. If you aren’t sure, and you think you might want to go do something else, Caltech is probably not the best place.

How many scientific papers do you have?

Close to 200.

What would be some of your advice for scientists today?

Think broadly, don’t be too constrained into narrow areas. Try to take advantage of new ideas, new technologies that come along. Whatever you are doing now will be out of date in 10 years. So you’ve got to be in a position where you can learn to expand on what you do and pick up new technologies as well as new ideas. The field is changing incredibly fast. Don’t get locked into doing one particular thing because it’s going to be out of date before you know it. And you’ll need to do something else.

What would you like to do after retiring?

I will stay intellectually involved, keep reading and keep going to the seminars. I still have a couple of papers to wrap up so initially I’m still going to be working part-time. I’m looking into different kinds of hobbies. I’d like to play piano and guitar a little more. I will also keep traveling. My wife (Dr. Susan Dutcher) is still active in science, and I will go to meetings with her. We were just in Turkey last September. We like to just travel to exotic places too. Last year we went to Ireland and we are going to Italy this coming year. We have grandkids on both coasts. Two grandkids on the East Coast and one on the West Coast. We’d like to see them when we can.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

I want to emphasize that every step along the way, everything I’ve done has been in conjunction with people around me. It’s been a group effort. Students, postdocs, and my collaborators all had a big influence. My advisor Larry Gold was influential for just letting me do this research which was very non-traditional and nobody else has done before. If I made a list of collaborators there would be another 20 people on the list that had a big influence on what I did. They all helped me in different ways, either generating data or having ideas, just lots of people.