Defects in motile cilia in humans cause the rare disease Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD), affecting approximately 1 in every 10,000 to 30,000 people. People who have PCD are characterized by recurrent respiratory infections, left-right asymmetry defects, ear infections, and infertility. Even with genome and exome sequencing, 30% of the patients still don’t have a gene that’s associated with their diagnosis. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, a single-celled alga, is commonly used as a model organism to study the genetic causes of PCD. In the new study recently published in PLOS Genetics, graduate student Gervette Penny in the Dutcher lab, sheds light on how PF23 dosage affects cilia assembly and regeneration.

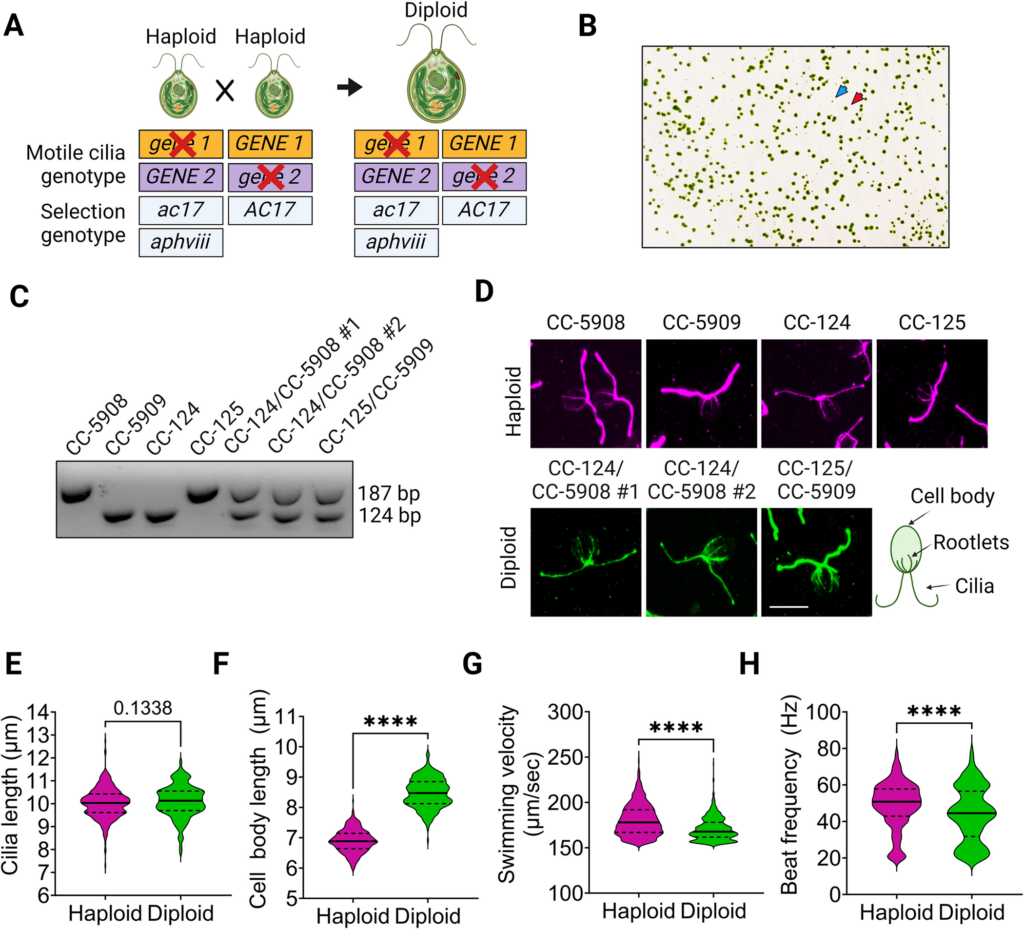

Most of the genes involved in PCD are recessive, meaning both copies of a single gene must be abnormal to cause the disease. The scientists set out to use another genetic model to study how motile cilia mutations can affect cilia function. Their design for the experiment centered on this question “can we see effects on cilia if there is a mutation in one copy of one gene and one copy of another gene, instead of having the mutation in two copies of a single gene?” Chlamydomonas is a haploid organism with only one copy of each gene. This is different from humans that have a diploid genome, and have two copies of every gene. To conduct the study, diploid Chlamydomonas mutant strains were created in the laboratory.

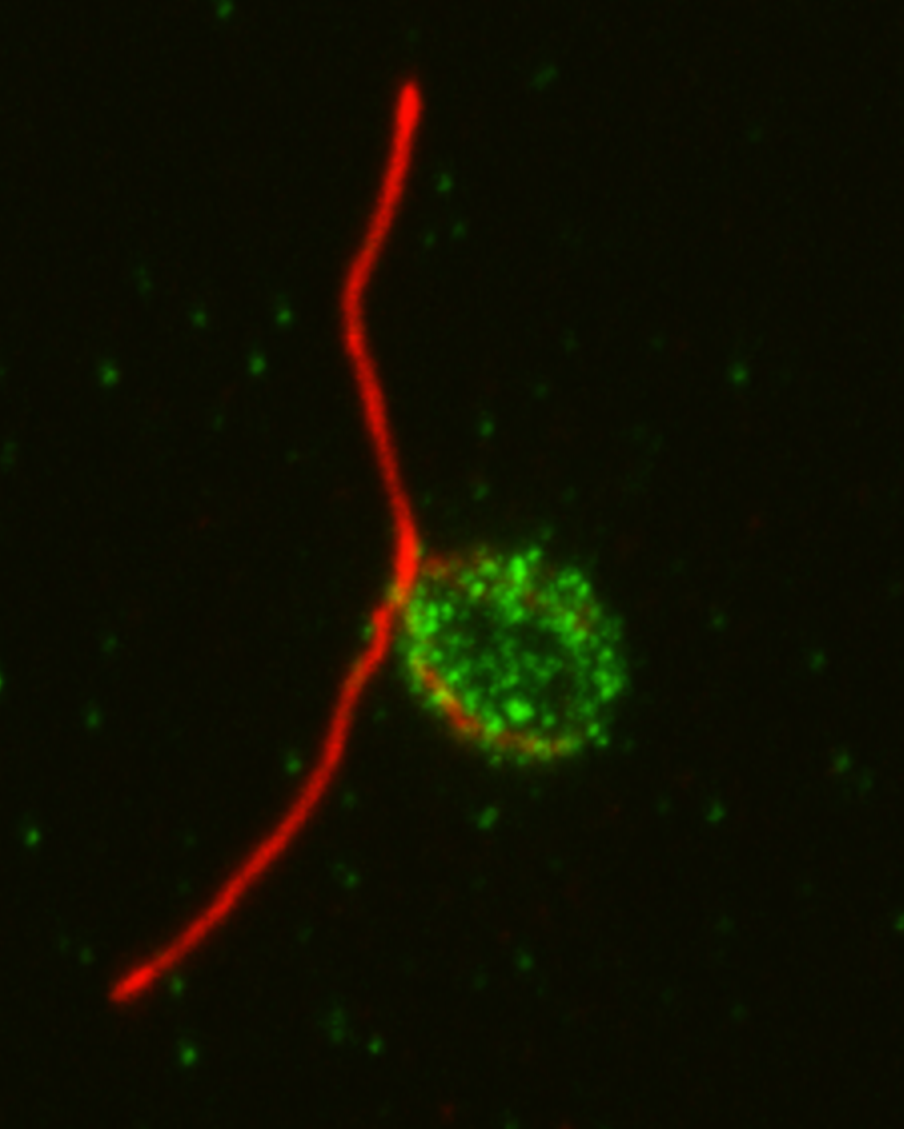

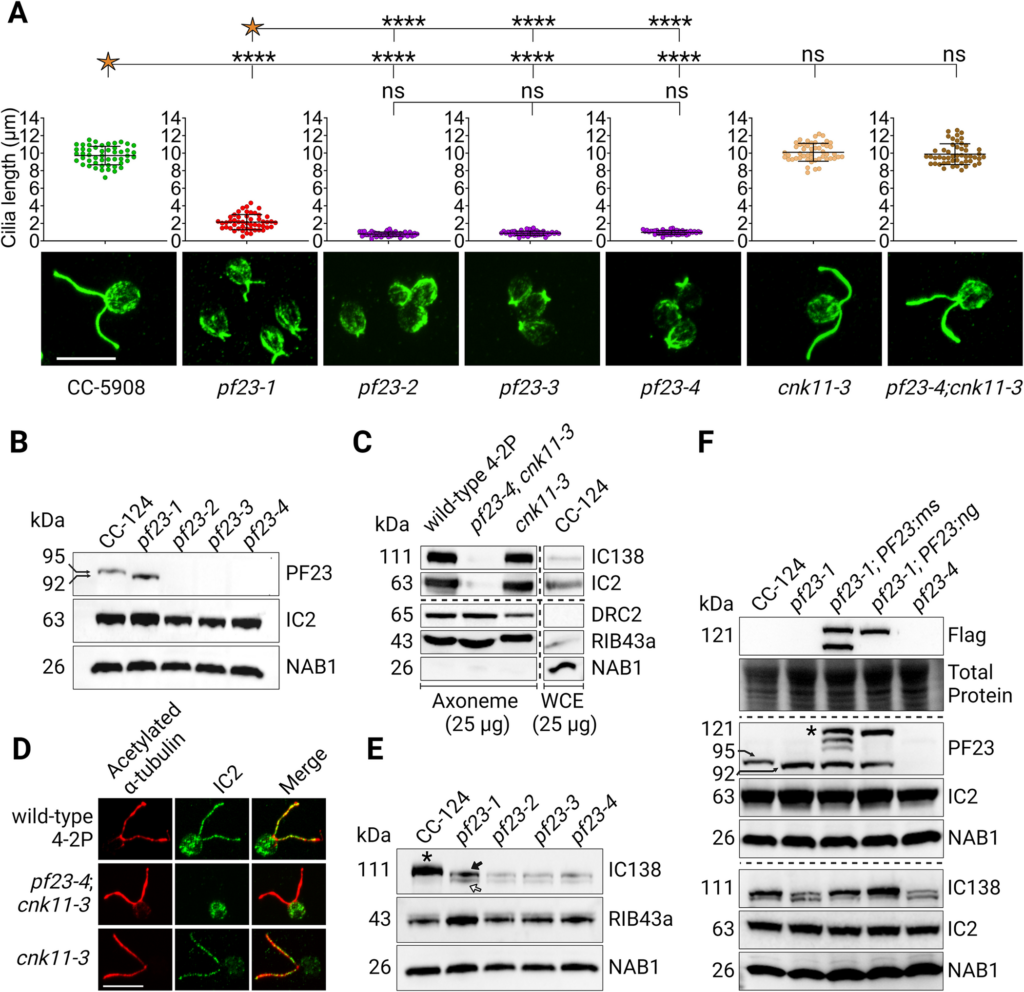

Surprisingly, scientists didn’t observe any phenotype with the diploids initially. “It was surprising because we thought we would see something that resembled the motility defects associated with the mutations found in the strains used to make diploids.” says Gervette Penny, PhD, the lead author of the paper. One unique feature of Chlamydomonas is that the cilia can be easily removed by pH shock. To further the study, researchers applied pH shock and protein synthesis inhibition to observe the regeneration of cilia using the cytoplasmic pool of proteins. Eight of the double heterozygotes that have at least one mutation in a cytoplasmic dynein preassembly gene assemble even shorter cilia than wild-type cells. Additional analysis found that PF23 dosage affects phenotype severity.

“There is still a lot that isn’t known about the assembly process of the dyneins. From this study, we learned that the dosage of the genes involved in cytoplasmic assembly is important. Even though we didn’t see a direct relationship between the genotypes of having the double heterozygous mutations and the phenotype immediately, it still has implications for human disease. Potentially, in some human patients, if they are subject to severe stress or some type of infection affecting their cilia while having these double heterozygous combinations, it could be harder for them to recover. Looking at double heterozygous genotypes for cilia mutation in humans is still relatively unexplored.” says Gervette Penny.

Featured in this article:

Gervette Penny, PhD

Gervette is from the Caribbean island of Grenada where she completed a BS in Life Sciences at St. George’s University (SGU). She conducted research in Dr. Susan Dutcher’s lab and received her PhD degree from Washington University in St. Louis in 2023. She is currently a postdoctoral researcher.

The Dutcher Lab

The Dutcher Lab investigates the assembly and function of basal bodies/centrioles and cilia using genetics, biochemistry, microscopy, and computational biology in Chlamydomonas as well as human tissue culture cells.